About Marie Tharp

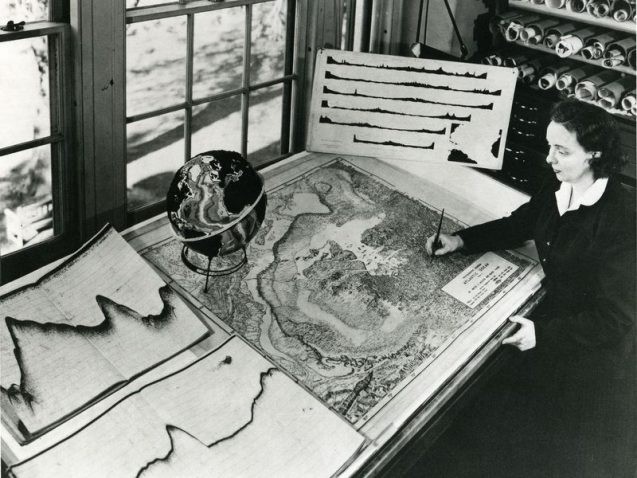

In 1948, when Marie Tharp began working at the Lamont Geological Laboratory (now the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University), very little was known about the structure of the seafloor; it was thought to be mostly flat and featureless.

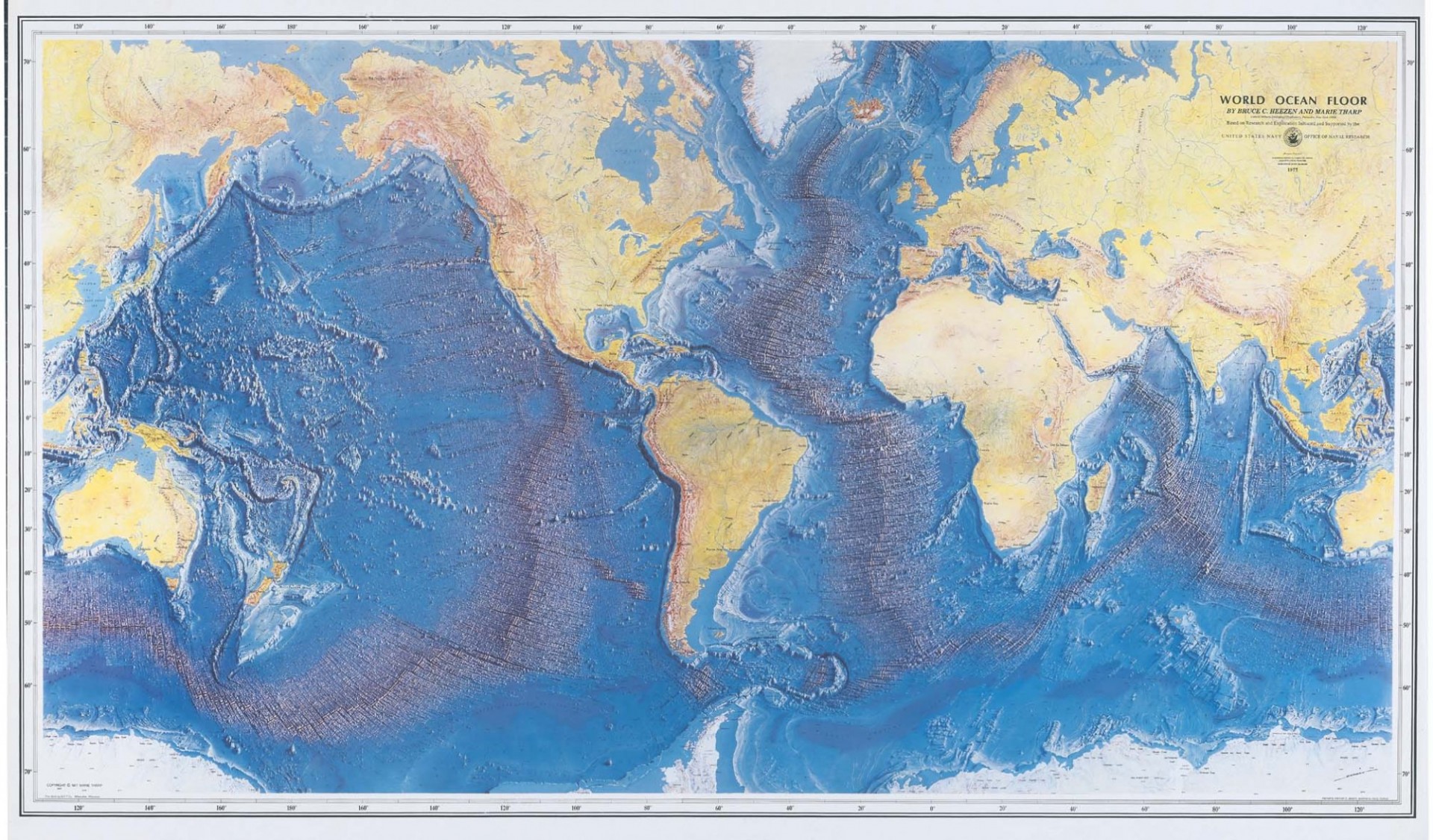

But when Tharp and her colleague Bruce Heezen published the first map of the Atlantic in 1957, Tharp’s drawings revealed that the seafloor is instead covered in canyons, ridges, and mountains. Over time, her maps revealed the existence of the mid-ocean ridges, a series of mountain ranges that extend over 40,000 miles around the globe.

In 1977, Tharp and Heezen published the first complete world map of the ocean floors. Their work helped to prove the theory of plate tectonics, the idea that the continents move over time, which was controversial until then. The discovery revolutionized our understanding of how nearly everything on the planet works.

Tharp began her career at a time when few women became scientists. Because of her gender, she wasn’t even allowed on the ships that collected the seafloor data that she used to make her maps; she didn’t set foot on a research cruise until 1968. Her early evidence of seafloor spreading was dismissed as “girl talk.”

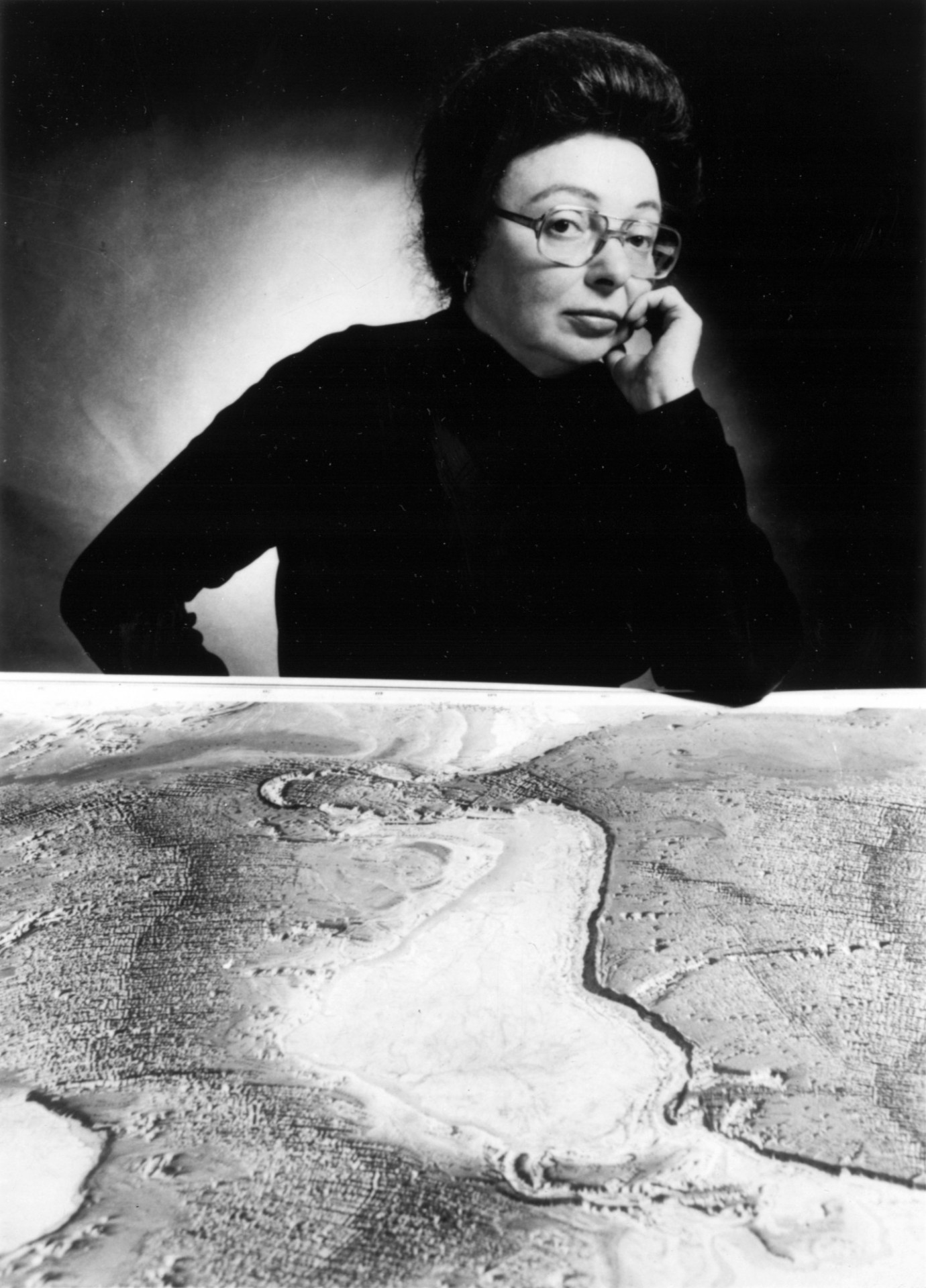

Today, Marie Tharp is recognized for the revolutionary that she was. In 1997, the Library of Congress named her as one of the four greatest cartographers of the 20th century. She died of cancer in 2006 at the age of 86, but her legacy lives on in the countless women scientists she has inspired.

Learn more: Marie Tharp’s Adventures in Mapping the Seafloor, In Her Own Words | Lamont’s Marie Tharp: She Drew the Maps That Shook the World | 8 Surprising Facts About Marie Tharp, Mapmaker Extraordinaire